Artificial intelligence to unlock sustainable development potential in Southeast Asia

Emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technology has the potential to accelerate ASEAN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) progress.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is one of the fast-growing regions in the world, but despite its success in economic development, its overall progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is worrying. Except for sustainable industry and innovation (Goal 9), progress toward the other SDGs has been lagging, particularly those related to environmental development, such as responsible consumption and production (Goal 12), climate action (Goal 13), life below water (Goal 14), and life on land (Goal 15) (UNESCAP 2021). Emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technology has the potential to accelerate ASEAN’s SDG progress.

Several studies (e.g., Galaz et al. [2021]; Korwatanasakul and Takemoto [2021, 2022]; Nishant, Kennedy, and Corbett [2020]; Sætra [2021]) have illustrated the benefits of AI applications for achieving the SDGs. Globally, AI positively affects 79% of the 169 SDG targets, including 93% of the environmental targets, 70% of the economic targets, and 82% of the social targets (Vinuesa et al. 2020). Economies such as the European Union (EU), Japan, and the United States (US), have leveraged AI to fulfil the SDGs, and ASEAN is no exception. Kearney and EDBI (2020) forecast that AI could contribute $1 trillion to the ASEAN economy by 2030.

Moreover, AI-enabled initiatives can improve environmental and social targets. For instance, Malaysia has implemented its “City Brain” initiative to improve urban planning and crime prevention (AI4SDGs Think Tank 2022). Meanwhile, in efforts to reach its health-related targets, Thailand has launched the “AiMASK” project to encourage mask-wearing during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic (Korwatanasakul and Lertpusit 2022); the “Doctor Raksa” project to offer telemedicine services (Kearney and EDBI 2020); and an AI program to improve diagnostic techniques for diabetic eye disease (IIC and TRPC 2020). For environmental development, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Viet Nam, with assistance from the US, have created an image recognition tool to monitor and control plastic waste management and ocean pollution (AI4SDGs Think Tank 2022).

Notwithstanding the benefits offered by AI applications, the inability to adopt AI technologies poses a significant challenge to ASEAN. While more developed economies are positioned to reap the benefits of emerging AI technologies, ASEAN is still lagging in terms of AI preparedness and AI resilience. AI preparedness refers to the ability of companies and consumers to seize opportunities emerging from AI, whereas AI resilience captures the ability of economies to adapt to structural changes due to AI and technological disruption (Pau, Baker, and Houston 2017). Thus, indicators such as investment and spending on AI technologies, AI innovation capacity, digital literacy and human capital, and data and infrastructure can potentially capture the level of AI preparedness. Similarly, government vision, governance and ethics, government digital capacity, and government adaptability can be proxies for AI resilience.

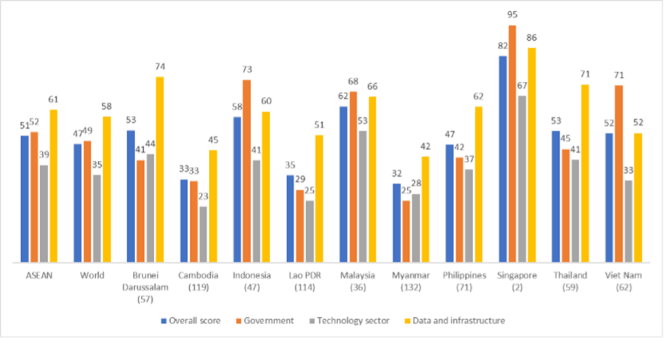

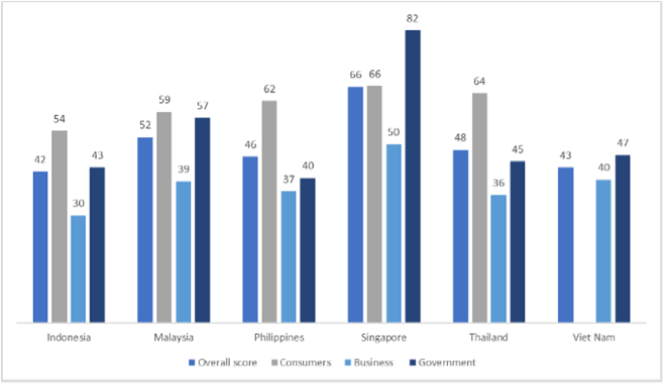

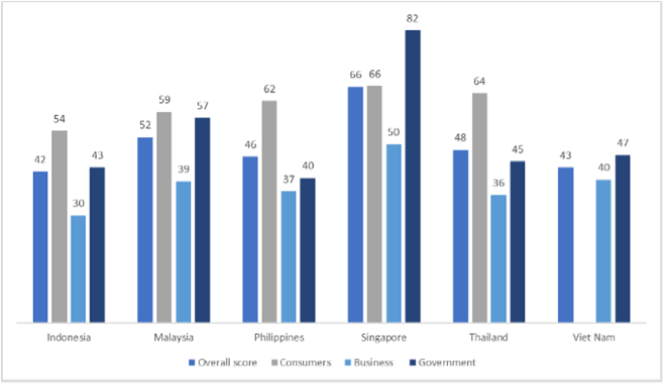

Figures 1 and 2 show the levels of AI preparedness (through indicators for “technology” and “data and infrastructure” in Figure 1 and “consumers” and “business” in Figure 2) and AI resilience (captured by “government” in both figures) for ASEAN and the world. Overall, ASEAN’s AI preparedness and AI resilience are just above the world average, signalling a slow adjustment to fast-growing AI technologies (Figure 1).

Meanwhile, AI preparedness and AI resilience levels vary across the ASEAN member states (AMS). Within AI preparedness, the levels for “data and infrastructure” (Figure 1) and “consumers” (Figure 2) are well above those for the “technology sector” (Figure 1) and “business” (Figure 2). This highlights the significantly large gap between the creators of AI technologies and the potential users (consumers) who are ready to adopt AI-related products and services. In other words, the development of AI technologies in the region is not keeping up with the potential AI users. In 2019, while the US spent $155 per capita investing in AI applications, AI investment in ASEAN was only approximately $2 per capita (Kearney and EDBI 2020), indicating ASEAN’s underinvestment in AI.

Figure 1. AI Preparedness and Resilience Index 2021 for ASEAN and the World

ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Lao PDR = Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

Note: The numbers in parentheses indicate the global ranking out of 160 economies. The maximum score for each pillar is 100.

Source: Oxford Insights (2021).

Figure 2. Asia Pacific AI Readiness Index 2021 for Selected ASEAN Countries

Note: The maximum score for each pillar is 100. Consumer readiness data are not available for Viet Nam.

Source: Salesforce (2021).

There also exists a wide gap between the advancement of AI regulations and policies (“government” in Figures 1 and 2) and the low adoption of AI technologies in the private sector (“technology sector” (Figure 1) and “business” (Figure 2)). This suggests an opportunity for ASEAN governments to lay a strong foundation for national AI strategies, AI governance and ethics (e.g., privacy legislation, cybersecurity, and national ethics frameworks), and government digital capacity and adaptability. Early implementation of national AI strategies and frameworks will guarantee the privacy and security of all relevant stakeholders and, in turn, encourage the adoption of AI in the public and private sectors.

Figure 3 illustrates the current situation of AI policy instruments in selected AMS. Singapore, one of the world leaders in AI, has adopted the highest number of policy instruments, covering the broadest range of policy categories, including governance, guidance and regulation, financial support, and AI enablers and other incentives. In contrast, the other countries’ policy initiatives are still limited, indicating progress only until the initial stages of policy planning and possibly implying a lack of government vision and insufficient digital capacity and adaptability. On the positive side, three of the observed countries explicitly include sustainable development in their AI national strategies and other policy instruments.

The findings indicate that ASEAN’s unsatisfactory levels of AI resilience and preparedness, particularly in the business and technology sectors, are preventing it from utilising AI technologies to achieve the SDGs. The challenges faced by the AMS include the business sector’s underinvestment in AI, the government sector’s impaired vision and inadequate digital capacity and adaptability, and the government and business sectors’ slow adjustment to fast-growing AI technologies and the expanding pool of potential AI users.

To respond to these challenges, governments should formulate national AI strategies for accelerating the development of fundamental AI policy frameworks while prioritising the adoption of AI in key sectors, and these efforts must strike a balance between ecosystem developments and regulatory approaches. Governments can also boost private sector investment in AI through incentive programs, such as for financial support and the creation of safe and secured cyberspace. Finally, these measures can be complemented by the promotion of education and capacity building programs introducing AI-related knowledge to further accelerate the adoption of AI technology among the public and private sectors.

Figure 3. National AI Policies and Strategies for Selected ASEAN Countries

Note: The total number of policy instruments is equal to the sum of “governance”, “guidance and regulation”, “AI enablers and other incentives”, and “financial support.” “Sustainable development” indicates the number of policy instruments explicitly discussing sustainable development.

Source: Authors’ compilation based on IIC and TRPC (2020) and OECD.AI (2021).

Author

Upalat Korwatanasakul

United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability

Dang-Dao Nguyen

Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences

Suonvisal Seth

Cambodia’s Lower House (National Assembly)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of their respective affiliations.

This article was originally published in the Asian Development Bank Institute’s Asia Pathways blog

References

AI4SDGs Think Tank. 2022. Projects Under Specific SDGs Topics. https://ai-for-sdgs.academy/topics

Galaz, V., M. A. Centeno, P. W. Callahan, A. Causevic, T. Patterson, I. Brass, S. Baum, D. Farber, J. Fischer, D. Garcia, T. McPhearson, D. Jimenez, B. King, P. Larcey, and K. Le. 2021. Artificial Intelligence, Systemic Risks, and Sustainability. Technology in Society 67.

International Institute of Communications (IIC) and TRPC. 2020. Artificial Intelligence in the Asia-Pacific Region. https://www.iicom.org/wp-content/uploads/IIC-AI-Report-2020.pdf

Korwatanasakul, U., and S. Lertphusit. 2022. Public Mask-Wearing Behaviour and Perception Toward COVID-19 Intervention Policies in Thailand: A Mixed-Methods Study. In Comparing Public Reactions to Wearing Masks in Asia and Europe: Public Behaviour to the State during the COVID-19 Pandemic, edited by N. Suzuki, M. Endo, and S. Annaka. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Korwatanasakul, U. and A. Takemoto. 2021. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development: Applying Social Principles for Human-Centric AI. https://www.eu-japan.ai/leveraging-artificial-intelligence-for-sustainable-development-applying-social-principles-for-human-centric-ai/

Korwatanasakul, U. and A. Takemoto. 2022. Friends or Foes: A Trade-Off Analysis of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Sustainable Development. Knowledge article, EU-Japan.AI.

Nishant, R., M. Kennedy, and J. Corbett. 2020. Artificial Intelligence for Sustainability: Challenges, Opportunities, and a Research Agenda. International Journal of Information Management 53.

AI. 2021. Database of National AI Policies. https://oecd.ai/en/dashboards

Oxford Insights. 2021. Government AI Readiness Index 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58b2e92c1e5b6c828058484e/t/61ead0752e7529590e98d35f/1642778757117/Government_AI_Readiness_21.pdf

Pau, J., J. Baker, and N. Houston. 2017. Artificial Intelligence in Asia: Preparedness and Resilience. Hong Kong, China: Asia Business Council. https://www.asiabusinesscouncil.org/docs/AI_briefing.pdf

2021. Asia Pacific AI Readiness Index 2021. https://www.salesforce.com/content/dam/web/en_au/www/documents/pdf/asia-pacific_ai-readiness-index-2021.pdf

Sætra, H. S. 2021. AI in Context and the Sustainable Development Goals: Factoring in the Unsustainability of the Sociotechnical System. Sustainability 13(4): 1738.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). 2021. Asia and the Pacific SDG Progress Report 2021. New York: United Nations https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/knowledge-products/ESCAP_Asia_and_the_Pacific_SDG_Progress_Report_2021.pdf